The Parting of the Sea

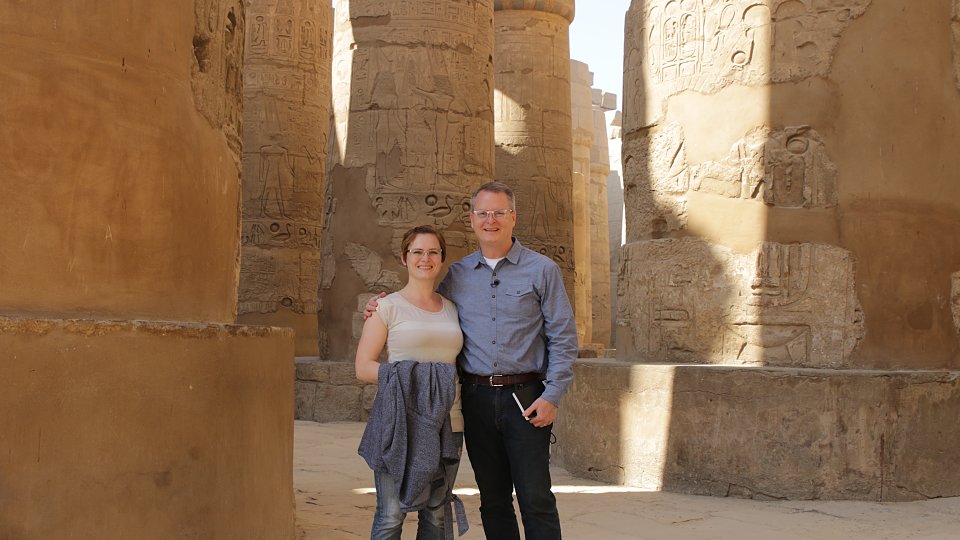

Today’s post is an excerpt from Chapter Three of my latest book, Moses: In the Footsteps of the Reluctant Prophet. Click here to read last week’s post, which was taken from Chapter Two. About the photos above: (1) Filming the small group video on the crossing of the Reed Sea on location near Ismailia, Egypt. This is one of the small lakes some scholars have proposed was the Sea of Reeds. The Suez Canal now cuts through the eastern side of the lake. (2) Pharaoh Ramses II in his chariot marching into war – from the exterior of the Karnak Temple in Luxor. (3) An actual chariot that belonged to King Tutankhamun and was found in his tomb. Depending upon when Moses is dated, Moses was likely a contemporary of King Tut. Today we pick up Moses’ story after Pharoah has freed the Israelites. Following the plague of the firstborn, Pharaoh released the Israelites, and they departed Pi-Ramesses in the middle of the night. Exodus 13:17-18 notes, When Pharaoh let the people go, God didn’t lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, even though that was the shorter route. God thought, If the people have to fight and face war, they will run back to Egypt. So God led the people by the roundabout way of the Reed Sea desert. In a strange turn of events, God commanded Moses to lead the people to set up camp in front of the Reed Sea. The Reed Sea is the literal reading of the Hebrew that is usually translated as “Red Sea.” To the Israelites, it must have seemed an odd place to camp. To the east was a marshy lake. To the west was Pharaoh’s Egypt. If for any reason Pharaoh should come after them, they would be trapped. But surely, they must have hoped, that would not happen. Pharaoh, hearing that the slaves had camped near the lake and now regretting his decision to let such a massive labor force go free, decided to go after them and to retrieve them as Egypt’s slaves. We read in Exodus 14:6-7, “So he sent for his chariot and took his army with him. He took six hundred elite chariots and all of Egypt’s other chariots with captains on all of them.” It was the elite chariots that made Pharaoh’s army so imposing. These were the latest in military technology. Examples of Pharaoh riding his chariot into battle can be seen in bas reliefs on the sides of many Egyptian temples that were built or expanded by Ramesses II. Amazingly, at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo you can see actual chariots used shortly before the time of the Exodus, which were wonderfully preserved in King Tut’s tomb. Exodus 14:9 notes, “The Egyptians, including all of Pharaoh’s horse-drawn chariots, his cavalry, and his army, chased them and caught up with them as they were camped by the sea.” Up to this point in the story, it had been Pharaoh and his gods with whom God had battled. Now, God was about to display his power against the greatest military power on earth at the time. We know from the battle of Kadesh, in which Ramesses II fought against the Hittites, that Egypt had several thousand chariots in addition to the six hundred elite chariots. The chariots were lighter and more advanced than those of other nations. One modern engineer described them as the Formula One racers of their time. Two horses would draw the chariot, which was piloted by one warrior while another, using Egypt’s advanced composite bows, fired at their enemies from a distance. As the charioteers drew closer, swords and spears were used. It is not difficult to imagine what the mostly unarmed Israelites were feeling as they saw the dust from Pharaoh’s chariots in the distance. The Israelites were terrified and cried out to the Lord. They said to Moses, “Weren’t there enough graves in Egypt that you took us away to die in the desert? What have you done to us by bringing us out of Egypt like this? Didn’t we tell you the same thing in Egypt? ‘Leave us alone! Let us work for the Egyptians!’ It would have been better for us to work for the Egyptians than to die in the desert.” But Moses said to the people, “Don’t be afraid. Stand your ground, and watch the Lord rescue you today. The Egyptians you see today you will never ever see again. The Lord will fight for you. You just keep still.” (Exodus 14:10-14) Nightfall came, and the Egyptians made camp opposite the Israelites. God commanded Moses to lift his staff over the water. That night a strong east wind came blowing across the water toward the Israelites, and when morning came they found the water pushed back by the wind on either side of a path that had been cleared through the middle of the sea. Using the path, the Israelites walked through the water as if on dry land. The Egyptians tried to follow, but their chariots appeared to become stuck in the seabed, slowing them down. When the Israelites arrived on the other side of the sea, God commanded Moses to stretch back his staff over the waters. When he did, the waters returned, covering the Egyptian army and charioteers. The finest army in the land was utterly destroyed. As the Israelites stood watching this scene unfold, they were undoubtedly filled with awe. They had been utterly delivered from Pharaoh and the greatest military power of the day. A rabbi friend describing the Passover Seder noted, “This is our defining story. If you are a Jew, you’ve got to get this. It defines who we are as a people. We were slaves. God saw our suffering. God delivered us and made us his own. This is our story.” When God chose a people with whom he would have a special covenant relationship, he selected a group that was oppressed and enslaved. He delivered them by his “mighty right hand.” There was nothing they could have done to deliver themselves. There’s a word that describes this kind of salvation: grace. It was salvation that the Israelites did nothing to deserve; it was purely an act of God’s kindness, mercy, and love. What does the story mean for Christians? It means that God cares about the nobodies! It means that God will ultimately defeat the arrogant, prideful, and cruel. It means that God sees our suffering, and God will deliver us. It means that we don’t have to remain enslaved to the things that bind us. God can set us free. Today’s post is an excerpt from Chapter Three, “The Exodus,” from my latest book, Moses: In the Footsteps of the Reluctant Prophet. Click here to find more information about all Moses products, including the primary book, a Leader Guide, a Children's Leader Guide, and a Youth Study book.