The Birth of Moses

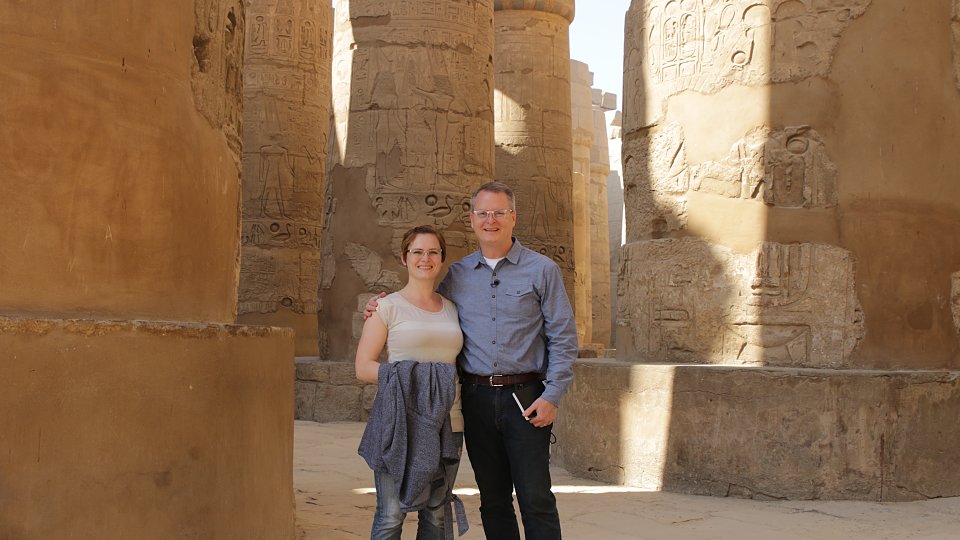

Today’s post is an excerpt from Chapter One of my latest book, Moses: In the Footsteps of the Reluctant Prophet. Click here to read last week’s post, which was taken from the book’s Introduction. Notes about the photos above: (Photo #1) My daughter Danielle and I in the Hypostyle Hall in the great Karnak Temple which was built during the time of Moses (if one assumes a 13th century date for much of Moses’ life). The hall is 54,000 square feet and is dedicated to the principle god of the Egyptian pantheon, Amun Ra. In the Moses small group video I take viewers through this temple complex. (Photo #2) One of the small sailboats visitors can take on the Nile in Luxor. Across the River are the Theban Hills within which is found the Valley of the Kings where the Pharoah’s during Moses’ period, and long after, were buried. I take viewers of the DVD inside one of these tombs. Now Joseph and all his brothers and all that generation died, but the Israelites were exceedingly fruitful; they multiplied greatly, increased in numbers and became so numerous that the land was filled with them. Then a new king, to whom Joseph meant nothing, came to power in Egypt. (Exodus 1:6-8 NIV) As seen in this Scripture, the backdrop for the story of Moses is the story of Joseph, the son of Israel, who was sold by his brothers into slavery and eventually became Pharaoh’s second-in-command over Egypt. The story is a masterpiece of ancient literature and is known by many who have never picked up a Bible because of the wonderful way Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber retold it in the hit Broadway musical Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. The biblical story actually fits well a period in Egypt’s history in which foreign people, known as Hyksos, settled in the Nile River Delta. These foreigners eventually gained control of Lower Egypt (the area from roughly Memphis north to the Mediterranean, including the massive Nile Delta) and ruled as pharaohs over the land for roughly a hundred years. The Israelites, like the Hyksos, were Semitic people. Both came from the Near East, and both were shepherds and farmers. It would not be surprising for a Hyksos pharaoh to make a Hebrew such as Joseph his prime minister and to allow the Israelites to settle in the land of the Delta with many other Semitic people. Sometime after Joseph lived, Pharaoh Ahmose I of Upper Egypt (the area from roughly Memphis south), who ruled from 1550 to 1525 b.c., led an Egyptian army to defeat the Hyksos and drive them from Egypt. Ahmose united Upper and Lower Egypt once again and began what historians call the New Kingdom period of Egyptian history. Ahmose I may have been the “new king to whom Joseph meant nothing” who “came to power in Egypt.” It would appear that the Israelites were not forced to leave Egypt with the Hyksos but allowed to remain. But the Egyptians had something else in mind for the Israelites. Pharaoh feared that the Israelites would join Egypt’s enemies, the Hyksos or other enemies from the east, and fight against Egypt in case of war, and he responded by enslaving the Israelites. Fear is a key word to remember in this part of Moses’ story. It is behind the oppressive treatment of the Israelites at every turn. Note what happens next: But the more they were oppressed, the more they grew and spread, so much so that the Egyptians started to look at the Israelites with disgust and dread. So the Egyptians enslaved the Israelites. They made their lives miserable with hard labor, making mortar and bricks, doing field work, and by forcing them to do all kinds of other cruel work. (Exodus 1:12-13) Notice that Pharaoh was the most powerful ruler on earth, king of both Upper and Lower Egypt, and yet he and his people were anxious about a minority population of foreign sheepherders in their midst. Their fear led them to despise the Israelites and to oppress them. In Egypt, as fears grew about the increasing population of Hebrews, so too did the oppressive acts ordered by Pharaoh. The king of Egypt spoke to two Hebrew midwives named Shiphrah and Puah: “When you are helping the Hebrew women give birth and you see the baby being born, if it’s a boy, kill him. But if it’s a girl, you can let her live.” (Exodus 1:15-16) The Hebrews had not rebelled. They had done no harm to the Egyptians. Yet fear led Pharaoh to decree this dreadful plan to kill newborn baby boys. Two Courageous Midwives The writer of Exodus goes on to tell us something profound about the midwives who were commanded by Pharaoh to put the infant boys to death at childbirth: “Now the two midwives respected God so they didn’t obey the Egyptian king’s order. Instead, they let the baby boys live” (Exodus 1:17). These women feared God more than they feared Pharaoh, and they refused to go along with his plan. Can you imagine the courage of these two women? This is one of the first recorded acts of civil disobedience in history. Because of their disobedience they saved the lives of countless children, perhaps even that of Moses. A Determined Mother and a Compassionate Princess When the midwives refused to kill the boys as they were born, Pharaoh gave an order to all Egyptians: “Throw every baby boy born to the Hebrews into the Nile River, but you can let all the girls live” (1:22). Can you imagine? He called the entire Egyptian populace to tear children from their mother’s arms and drown them in the Nile. And this is the context for the story of Moses’ birth. Now a man from Levi’s household married a Levite woman. The woman became pregnant and gave birth to a son. She saw that the baby was healthy and beautiful, so she hid him for three months. When she couldn’t hide him any longer, she took a reed basket and sealed it up with black tar. She put the child in the basket and set the basket among the reeds at the riverbank. The baby’s older sister stood watch nearby to see what would happen to him. (Exodus 2:1-4) Moses’ mother was Jochebed, a courageous woman who was not going to let her child be put to death. She refused to let her son die without attempting to save him. She hid him for three months, then took a basket made of reeds and she put her child in it and placed him among the reeds on the banks of the Nile. She did so at a location where Pharaoh’s daughter was known to bathe, perhaps in hopes that the daughter would feel compassion for the child, disobey her father, and save the child. I want you to notice that this is the Bible’s first story of adoption. Jochebed gave her child up for adoption in order to save his life. It was love that led her to give up the child; it was the only way she felt she could save him. Let us also consider Pharaoh’s daughter. We don’t know anything about her except that she saw the Hebrew child and, despite knowing what her father had decreed regarding Israelite boys, felt compassion and pity for the child and was moved to adopt him. How easy it would have been for her to have left the child there in the basket on the banks of the Nile, perhaps fearing her father or believing that surely someone else would save him. But instead her compassion led her to lift the child from the water, risk her father’s wrath, and take him home, adopting him as her own child. Of the four courageous women who saved the baby Moses, Pharaoh’s daughter was the least likely. She was the daughter of a despot who was oppressing and killing Israelites. She worshiped the Egyptian gods and goddesses. Yet God used her, as Moses’ adoptive parent, in one of the most important roles played by any mother in human history. Today’s post is an excerpt from Chapter One, “The Birth of Moses,” from my latest book, Moses: In the Footsteps of the Reluctant Prophet. Click here to find more information about all Moses products, including the primary book, a Leader Guide, a Children's Leader Guide, and a Youth Study book.